Upcoming Events

No event available, please check back again, thank you.

Latest Articles

HOW TO: Avoid Muay Thai Injuries

9 February 2020

TFC Sports Science Review

By Ben Johnston 2020

Edited by Sandy Pelenyi

Overtraining is a challenge that all sportspeople face and impacts professional athletes and amateur competitors alike. Optimising your training potential and avoiding injury is a crucial balancing act for anyone serious about sports and performance. You may be a competitive fighter or simply someone with an active lifestyle, nonetheless, avoiding injury and unnecessary fatigue so you can train at your full potential is paramount. Here are your questions answered about the impact of overtraining and some guidelines to keep you off the sidelines.

-

1 What are overtraining injuries

Overtraining injuries are musculoskeletal injuries that occur due to more activity or exercise than your body is used to. This may happen to anyone who increases intensity or changes type of activity.

- Q – How do I avoid injury from overtraining?

- A – Increase you weekly training load by no more than 10% each week!

How can I achieve this?

The negative impact of overtraining is widely studied in sports medicine and physiotherapy fields. The latest research shows that monitoring your training load using the acute:chronic workload ratio (ACWR) is an effective method to achieve high performance and avoid injury.

-

2 What is acute and chronic workload

Workloads can be specifically defined as;

- Acute workload: amount of loading completed within 1 week of training.

- Chronic workload: average workload each week over 4 weeks.

The ACWR takes into account the current training load (acute) and the training load that an athlete has been prepared for (chronic). This can be modulated depending on the athlete’s requirements.

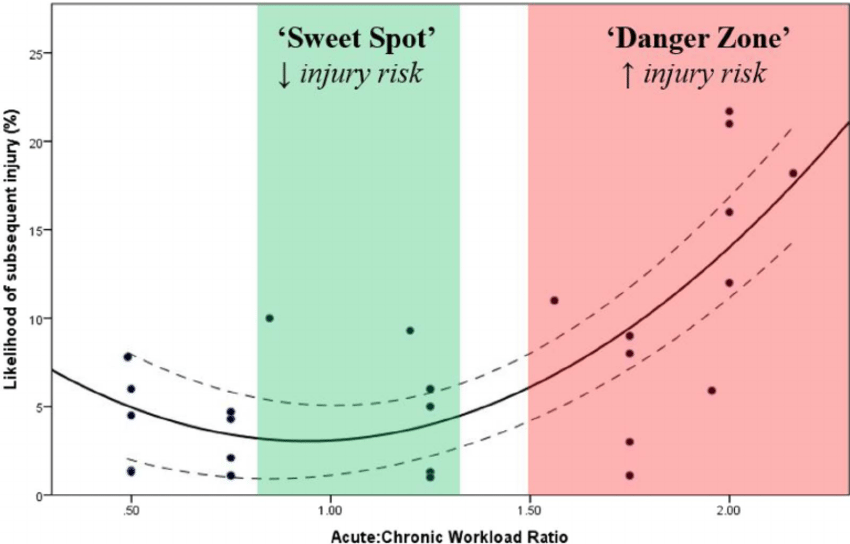

We want to use the ACWR to maintain the ‘sweet spot’ (Figure 1, green-shaded area) where injury risk is lowered, and performance is improved.

Figure 1. The green-shaded area (‘sweet spot’) represents acute:chronic workload ratios where injury risk is low. The red-shaded area (‘danger zone’) represents where injury risk is high. To minimise injury risk, practitioners should aim to maintain within a range of approximately 0.8–1.3. Image from Gabbett, 2017 (6).

-

3 How does it work

Adequate workloads are necessary to induce beneficial physiological adaptations such as high aerobic capacity, optimal body composition and increased strength.

Workloads that are too low may not only decrease performance but may result in lower levels of fitness and preparedness, subsequently increasing injury risk. In other words, the way the workload is applied over time is the predictor of injury risk. To summarize;

- High acute workload = increased risk of injury

- High chronic workloads = potential preventative effect

The ACWR aims to increase chronic workload in order to improve fitness and protect from musculoskeletal damage. The mechanism by which this occurs is progressive overload, which is the gradual increase of stress placed on the body during training.

An illustration of Milo of Croton, the ancient Greek wrestler who carried a calf until it grew into a bull, gaining strength along the way. The story is used as a way to explain the concept of progressive overload.

-

4 How do I calculate my ACWR

To determine your ACWR, firstly you must find your acute and chronic workload values.

Acute Workload (AW) Formula

Exercise (minutes) x intensity of training (%)

Here is an example;Monday: 60 min x 8/10 intensity

60 x 8 = 480Tuesday: 90 min x 6/10 intensity

90 x 6 = 540Wednesday: REST Thursday: 45 min x 9/10 intensity

45 x 9 = 405Friday: 60 mins x 5/10 intensity

60 x 3 = 300480 + 540 + 405 + 300 = 1725

Acute workload = 1725

Chronic Workload (CW) Formula

AW (Week 1 + Week 2 + Week 3 + Week 4) / 4Week 1: 1500 Week 2: 1600 Week 3: 1700 Week 4: 1725 1500 + 1600 + 1700 + 1725 = 6525

6525 / 4 = 1631.25Chronic workload = 1631.25

Now that we have these values, we can calculate the ACWR.

ACWR Formula

AW / CW

Acute workload = 1725

Chronic workload = 1631.251725 / 1631.25 = 1.06

Therefore, your ACWR value is 1.06.

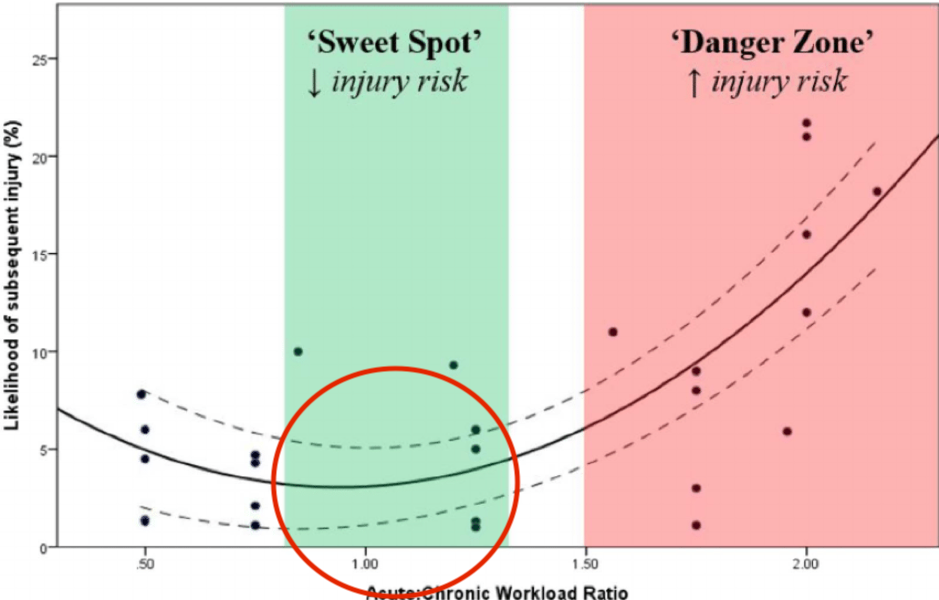

Now you can find your ACWR, but what does this mean? Figure 2. below again shows the ‘Sweet Spot’ and highlighted in the red circle is the optimal ACWR, which is between 0.8 and 1.3. It is essential for your ACWR to remain within this range. Lower may result in undertraining, and higher may result in injury.

Figure 2. Highlight of ACWR optimised value range (circled in red). Image from Gabbett 2017 (6). -

5 How to utilise ACWR to increase performance

Increase your weekly training load by no more than 10% each week!

As aforementioned, this should be achieved using progressive overload by increasing training in increments of 10% over a series of weeks in order to achieve the required fitness level, rather than attempting it all at once. This can be monitored using your ACWR and maintaining a 1:1 ratio (i.e. between 0.8 and 1.3). For example, if we have a CW of 1000 but require an AW of 2500 in order to be prepared for a fight, we need to increase to this over an order of weeks rather than a high spike within one week.

If we attempt the increase within one week, this is what happens to the ACWR;

2500:1000

ACWR = 2.5.

This value is significantly higher than 1.3, therefore the risk of injury is increased. By increasing training load by 10% each week, the ACWR remains around the 1.1. This also provides space for error if you have a particularly hard session that you didn’t plan on having, or if training runs over time.

This also means returning from injuries needs to be planned out properly, as missing training for a few weeks to recover seriously affects your chronic workload. Returning to a full training schedule could leave you at serious risk of injury, therefore load management to rebuild fitness is crucial.

-

6 What happens if I ignore my training workload

Extensive studies in various sports ranging from cricket, rugby and MMA support the monitoring of training and workload to prevent injury and enhance fitness.

A 2015 study examined elite rugby league players over 2 years. During the subsequent 2 years, a workload model was used to predict injuries, showing that players who exceeded the weekly workload threshold as determined by the model were 70 times more likely to test positive for non-contact, soft-tissue injuries, while players who did not exceed the threshold were injured 1/10 as often. Collectively, these data plus various other studies indicate that there is an increase in injury risk with absolute workload increases (5) (8).

-

7 Limitations of ACWR

ACWR is a widely accepted monitoring method in sport that performs reliably, however there are some limitations. These are primarily in regard to accuracy in collection methods and parameters of the working ACWR model. Refer to reference for more information (9).

-

8 Summary

Monitoring and adapting chronic workload are one of many facets involved in improving your performance as a fighter. Building a plan that factors in the ACWR that is specific to your personal goals may assist in enhancing your performance and decreasing your risk of injury.

For a more comprehensive review of ACWR, visit https://www.scienceforsport.com/acutechronic-workload-ratio/

This post is the expanded version from a segment found in The definitive guide for Beginners Starting Muay Thai. Head over there for more ways you can fast track your success!

Keen on hearing what our students’ experiences have been like? Find out directly from one of them here.